Gothic defined

Author: Flosha

What is Gothic?

In order to create a gothic drama we have to define what “Gothic” is.

Gothic is much more than the game that was released. It was once supposed to be very different (as shown in the “Vision of Gothic”); the underlying concepts from 1997-1999 were much more radical than what has been realised in 2001. These early ideas in their radicality fascinate us more than the actual game. And we go as far as to claim that it was an attempt to initiate a genre of gothic-like games and to revolutionise the world of fantasy RPGs.

We will not speculate about the reasons here, why Gothic turned out to be so different compared to the early vision of the game. We know that in some regards this happened under the pressure of time and due to technical issues and problems in design (such as with the multiplayer mode). But in other regards the developers changed the design direction willingly and we do not want to blame them for doing so; to quote Avallach: “it is just us who personally disagree”.

In the beginning we will analyse the meaning of “gothic” as a term and the gothic aesthetics and will make concrete examples of gothic-style in other media to highlight common characteristics.

We will then analyse Gothic as “another kind of fantasy”, compare gothic fantasy with common fantasy, deal with the concept of low fantasy and with horror or terror as aspects of gothic.

Based on the research of diverse documents and interviews as summarised in the collected quotes in the “Vision of Gothic” we’ll describe principles of gothic-like game design in the historical context of game development and the evolutionary roots of Gothic in the immersive sims preceding and inspiring it; we will compare this vision of a game with the game that was released, with games of similar character and with titles of the same franchise in context of the design principles of gothic-like immersive sims.

Summarising our findings we will then define “what Gothic is”, both as a genre and as the actual game that was envisioned in 1996 to 1999 and as it finds expression in the PHOENIX project.

Gothic Aesthetics

Among the fans of the official Gothic franchise there is a large amount of people who love Gothic only for the immersive gameplay and lore characteristic for it (or what remained of it in the release version), while they do not consider actual gothic aesthetics as anything essential. In other words: They love Gothic not for how “gothic” it is.

We think that this perspective is quite limited in that it excludes essential characteristics of what Gothic as a game should have been according to the early design direction and what “gothic” as a term is by definition. A complete definition of Gothic cannot be given without gothic aesthetics, the particular “style” strived for and hinted at with the very name “Gothic”.

The demo of the Mad Scientists, - that would later lead them to cooperate with Piranha Bytes and to develop Gothic’s Engine - had the working title “Finster” (German for gloomy / dark), which was already a clear hint for the dark style aimed for from the very start. And in fact it was one of them, Bert Speckels, who suggested “Gothic” as the name for their game, which is just a fitting and more international sounding title with a similar connotation as the original German one.

But many insisted on the notion that Gothic as a game has nothing to do with gothic as a term. They think it was just a cool sounding name without any relation to the associated cultural and aesthetical implications - and this is wrong. Gothic is both inspired by historical Goths as well as by gothic fiction and even the modern goth subculture. We have to conclude in the words of Avallach, that the early Gothic in fact…

takes inspiration from many different dimensions of “gothicness”.

In our lore documentation the actual goths from early medieval times will play a role and will be pointed out as an inspiration, but here we want to focus on gothic as a style.

Gothic Fiction

Gothic fiction is based on a romanticised view of the past, of decay, of the signs of time. Destruction, ruins, rust and patina are what gothic stories are clad in. In this regard we compare gothic as a visual style to the japanese wabi-sabi aesthetics, with the difference that gothic contains horrific or terrific elements and that the very style that is idealised in wabi-sabi and romanticised by gothic authors is here at the same time used as a fabric for the terror of the story (and in a game of the simulated world and life).

In 04/2000, Terrorian released a preview on zoks.de, titled: “GOTHIC - The Aesthetics of Evil” of which we quote a few meaningful lines:

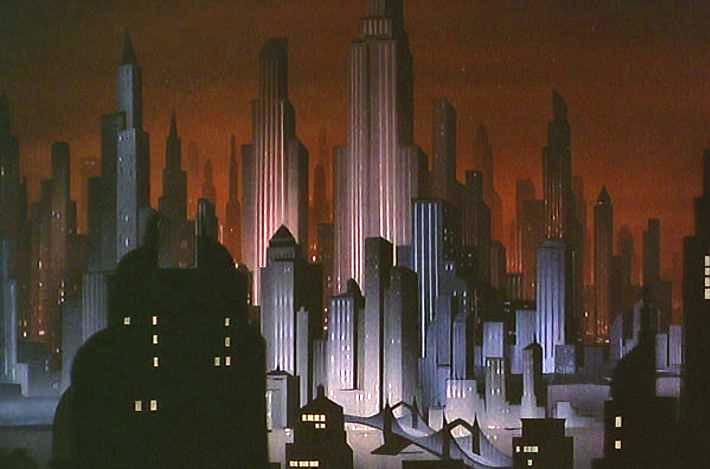

Fragments of “Gothic” are night scenes, wild landscapes, dungeons, ruins, monasteries, castles, vaults. Unexplainable crimes, invocations or ritual sacrifices happen there, hidden powers, mad scientists and dark tyrants are at work, visions, dreams, fears and supernaturals play jokes on human sanity. Short: The irrational, supernatural and incomprehensible along with its emissaries line up to deride the enlightened mind, the rational intellect of man. If we want to grasp it very modern, Batman’s Gotham along with its villains (Joker, Two-Face), who sit in the Arkham Asylum most of the time give an excellent picture of “Gothic”.

The Gothic story Sleeper's Ban by Alex Wittmann (described by Tom as "Punk, Physician, Surgeon, Roleplayer, Fantasy-Freak, Friend"), that was once supposed to become an official novel to the game, which is full of "shocking" descriptions (in German, gothic novels are described as "Schauerromane"), can also be seen in this very tradition as a mixture of gothic novel and fantasy book or short: as gothic fantasy.

Gothic Architecture

One of the typical traits of gothic fiction that inspired the same, is gothic architecture.

In Gothic the game there is not much - but some - actual gothic architecture to be found. The typical medieval ruins, old castles and so on - they are everywhere, but they are more early medieval in character. But there are a few examples of actual gothic architecture in the game. We can see the form of the doors in the mages chapel as simplified gothic arches. Avallach speculates that they would have been rounded a bit more but had to be simplified to remain low poly. And this speculation is confirmed by the Gothic Comic, where there are two typical tall, narrow gothic windows in Corristo’s chamber.

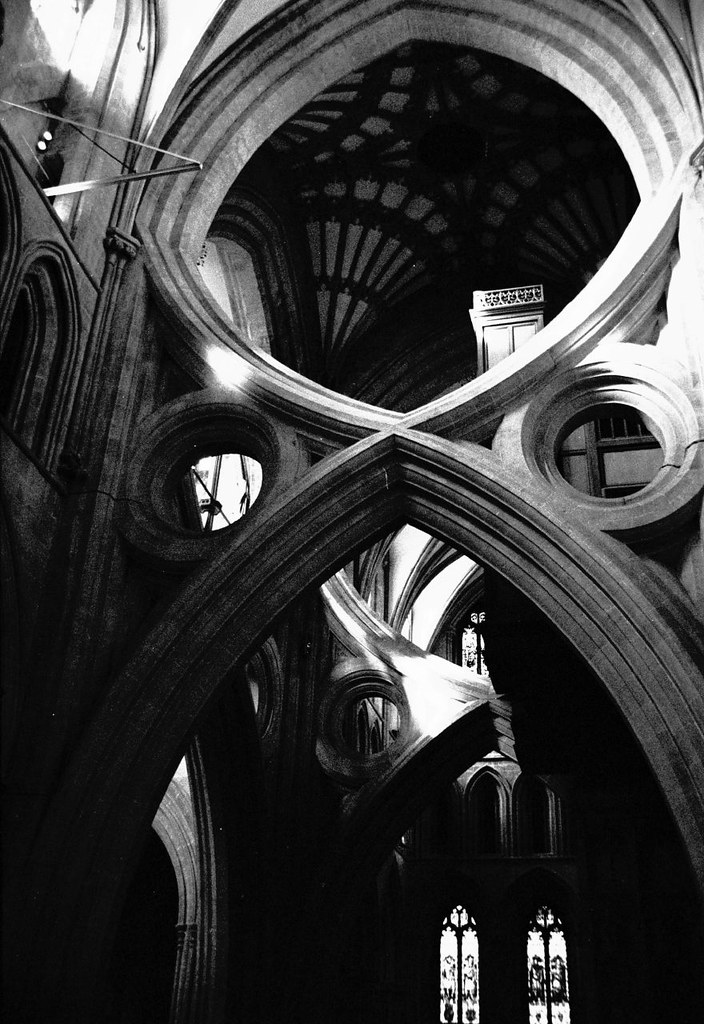

Then there are the iconic spikes on the towers of the prison castle and smaller ones on the chapel again, which Avallach sees as simplified “pinnacles” - they are another typical element of gothic architecture. And finally, there are so called “Scissor Arches” in the ancient temple, in the citadell close to the halls of the Sleeper, almost exactly as they are found in the Wells Cathedral:

The term “Gothic architecture” originated as a pejorative description. Giorgio Vasari used the term “barbarous German style” in his Lives of the Artists to describe what is now considered the Gothic style, and in the introduction to the Lives he attributes various architectural features to the Goths, whom he held responsible for destroying the ancient buildings after they conquered Rome, and erecting new ones in this style.

It was called German style, while it actually originated in France. And it had nothing to do with the Goths either. But nonetheless it was perceived as such for a long time.

“Gothic architecture” originally meant “barbarian” because it was replacing the “classic” architecture of the Roman empire after it’s fall. It became associated with the barbarian tribes of the Goths, as Goths were used as a symbol of barbarism. They were a major reason for the fall off the empire. To simplify it: A new architecture appeared and while not actually used by barbarians it reminded people of barbarians because it replaced the classical imperial Roman design. The barbarians most famous for robbing the empire, were Goths, so to show contempt and hate for this architecture the “fans” of the classical Roman architecture called it “gothic”. At that point “gothic” meant primitive, evil and cruel. Nothing nice at all. But in reality it was more architecturally advanced, as buildings could be made much, much taller without collapsing. (Avallach)

This “gothic” architecture again, was then - later by the romantic movement and by gothic fiction - used in those idealising ways, when the medieval times were seen positive again (Romanticism revived so-called “Medievalism”, after the middle ages were seen so negative in the renaissance - and medievalism plays a big role in modern fantasy). Actually, a new form of “Dark Romanticism” evolved from the romantic movement (which we could also describe as a pessimistic form of Romanticism; one of their most popular representatives was Edgar Allan Poe). And dark romanticism is closely linked to Gothic fiction. In this context it seems a bit absurd that the very term “romantic” refers to the romans or “the roman manner”, in opposition to the paganism that they actually emphasized; the rationalists before them where much more in favour of the romans. But now these ruins of old gothic buildings were seen as monuments of an old, dark, cruel and yet monumentally impressive past that inspired their fantasy and gave rise to all their dark and melancholic stories.

To me personally a very important idea of “gothic” is this trope of a fallen empire and its lost greatness. And of barbarism that threatens the final destruction of an ancient civilisation. (Avallach)

Gothic in Other Media

Gothic comes in various forms.

There is typical Christian medieval gothic, there is Victorian gothic (American McGee’s Alice), sword-and-sorcery-gothic (Gothic) or gothic-with-guns (Gloomwood); there is futuristic or contemporary gothic (or both, as in Matrix), cyber-gothic (e.g. Peripeteia), industrial-gothic (STALKER), southern gothic (True Detective) or oriental gothic (Prince of Persia: Warrior Within). Gothic aesthetics, moods and themes can be mixed with everything.

On this ground it has to be acknowledged - though it seems hard to grasp for many - that there are projects that play, e.g. in a futuristic or contemporary scenario but have more in common with the aesthetics of Gothic - because they share general aesthetic principles and themes with Gothic - than diverse medieval scenarios, when they are not gothic in style.

Gothic was developed under the influence of a time that also brought us Matrix (1999), a mix of contemporary (simulation) and futuristic (reality) gothic. It does not come as a surprise that the devs posed in long black coats (such as Mike Hoge here) for previews of the game - just as the Wachowskis were in that very scene (in fact, the club where Neo mets Trinity was a club they themselves went to, listening to industrial metal such as Ministry…). In MATRIX the whole crew of the Nebuchadnezzar wears typical gothic / punk fashion; they are rebels, techno-anarchists dressed in dark-scene clothing. There is the Merovingian residing in his castle with vaults of vampire programmes underneath, running gothic clubs full of fetishism.

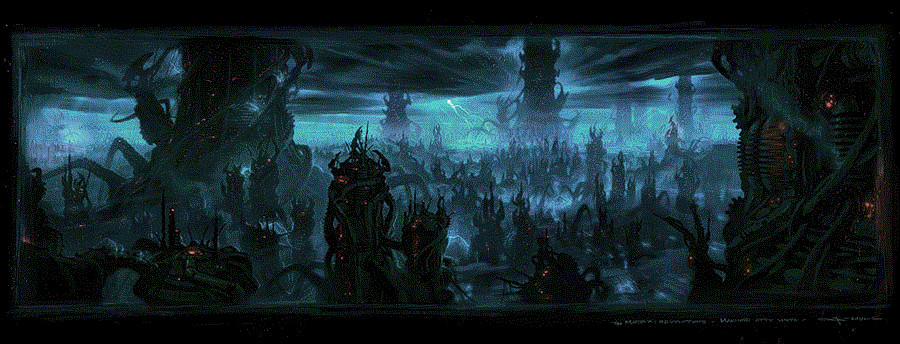

The Real World is a terrific dystopia where there is always darkness due to the veiling of the sky to block light as the machine’s energy source. Only the ruins of the former human civilisation remain. And the Machine City is like a futuristic vision of fields full of cyber-gothic cathedrals.

There is John Carpenter’s Escape from New York (and Escape from LA), which, as should be well known, was a major inspiration for the setting in Gothic. Avallach remarked: “It’s not just about the idea of an isolated rebelled prison colony. It’s about a specific kind of anti-government 90s dystopia.” The setting is described as an “island on the border of civilization, a no-man’s land of chaos, anarchy and darkness” and as an “island of the damned”. And there are even visual similarities, like the characteristic approach to sky colouring that will feel very familiar (if one knows the alpha screenshots of Gothic):

There is STALKER, which is contemporary industrial gothic, where the medieval ruins of gothic castles are replaced by old factory complexes shut down after the nuclear disaster. Style and themes are extremely similar to the ones in Gothic; the centre of the zone as the source of Psi Emissions - like the Sleeper in the Colony; the monolith as a cult to protect that center and being under control of the C-Consciousness to serve its will - like the fanatics in the brotherhood of the Sleeper. In fact, stylistically as well as thematically STALKER shares more with GOTHIC than any official “Gothic” successor.

There is American McGee’s ALICE which was described as a “Gothic Alice”, it is Victorian gothic in style. There is THIEF whose setting is a mixture of medieval and industrial gothic. Not to mention titles such as Shadow Man (gothic horror), Max Payne or Max Payne 2, subtitled as a “film noir love story”, which, to make it simple, is just the French way of saying gothic.

It is no wonder that gothic as a style seemed to dominate especially in the video game “industry” at that time when gamers were still considered kind of as outsiders. It was in vogue at the time. I am sure that the amazing oriental-gothic styled Warrior Within (2003) would have been appreciated more when released in 1999.

When analysing gothic as a style, I realised how gothic is perhaps the essential factor that so many titles I like have in common. I love MATRIX, ALICE and STALKER. And I loved novels such as Wuthering Heights, while not being aware that it is a typical gothic novel. I also was very fond of True Detective, which, as I later found out, is southern-gothic in style.

Gothic Subculture

It is also very likely that the Piranhas are Ex-Goths. And Goths are essentially the withdrawal of a romantic subculture that was weary of the political struggles of the punk / autonomous scenes. (04/2000, GOTHIC - The Aesthetics of Evil)

Goths or not, the early Piranha Bytes had a background in the black scene. In an interview for gamespot.com from 15.06.1998, Tom Putzki specifically remarked this relationship himself:

Delekhan: “GOTHIC” is an interesting choice for the name of your game. Is it just a working-title or the actual title?

Tom Putzki: […] GOTHIC is the actual title of our game. I like that kind of music and people, the black scene. It’s dark, gloomy, mysterious, creepy and magic - that’s GOTHIC.

It is true that the old Piranha Bytes (the original visionaries of Gothic) were punk and goth in character. And while the gothic scene may not be the primary stylistic influence, it is still connected with it, just as the subculture evolved from the very literary influence of gothic novels and their romanticising view on decay and, in the end, of death itself, that inspired the art direction of Gothic.

For instance, there were the “Gothic Girls”, girls selected in a competition to represent GOTHIC at promotional events. They posed in gothic clothing - in typical black leather - and the slave girls inside of the game were designed accordingly, clearly “gothic” in style.

But also the character design in general, especially in earlier versions of the game, was clearly inspired by the modern gothic subculture, which can still be seen in the official Gothic Comic, where almost every warrior runs around with studded leather belts around their naked upper bodies, such as Gorn; the very same style that you would find in 90s gothic clubs, like here in the club from The Matrix.

Gothic Fantasy

GOTHIC is supposed to be “another kind of fantasy” according to a promotion booklet from 1999:

Common Fantasy is very simple (…) divided into black & white, good & evil. Fantasy is neat, clean and colourful. GOTHIC is different. GOTHIC is gloomy. GOTHIC is dark. GOTHIC is mystical. GOTHIC is strange. GOTHIC is dangerous. GOTHIC is not a 3D-realtime-Fantasy-RPG. It’s a 3D-realtime-GOTHIC-RPG. (Promotion booklet)

As Avallach put it, the quote above “exactly shows what went wrong” with the official successors in the franchise. Based on these descriptions we deduce several characteristics of Gothic as “the other kind of fantasy” that we will explain further below.

Thus Gothic is…

[to be seen in opposition to common fantasy, as...] * amoral, it is beyond good & evil and without a clear good / evil dichotomy * anarchic, it is not neat, it is disordered and deals with chaos * dreary, neither colourful nor clean, it is dirty and full of faded colours * different, it differs from what is commonly found in fantasy games [dark and low fantasy combined, in that it is...] * gloomy with a depressing mood, visually and narratively * dark in its style, its story; aesthetically and thematically * mystical, mystic / occult things in a world where magic is special, not common * strange in its setting, with unusual creatures and events to raise questions * dangerous in its atmosphere and its world design with both being coherent

Isn’t what was criticised here as “common fantasy” usually referred to as “high fantasy”? And isn’t the description of Gothic as another kind of fantasy fitting to what is now commonly referred to as “dark” fantasy?

GOTHIC is dark fantasy, which hints at its horror elements and its characteristics of being “dark”, “gloomy” and “dangerous”, but not every dark fantasy work is “gothic”. Some authors may use the terms “dark fantasy” and “gothic fantasy” or “gothic fiction” interchangeably, but it being “dark” doesn’t suffice to make it “gothic”. Gothic fiction has some essential characteristics that are not to be found in most mere “dark fantasy” fiction, as already hinted at in the previous chapter.

Gothic fiction is by definition romantic (in the traditional sense). One of its core features is “the intrusion of the past upon the present”, “the present being haunted by the past”. Gothic is not gothic without this threatening past as a crucial element both for atmosphere (how the game world is presented where time has taken its toll on everything) as well as for the story (e.g. how the past of characters is haunting them, how the consequences of the war haunt the present kingdom, how ancient rituals and prophecies play a role in the tragedy of today).

Thus it is also…

* romantic * melancholic * terrific, in the sense of terrifying / dreadful

Gothic fantasy necessarily consists of this particular visual and narrative style and the associated atmosphere that is characteristically gothic; while the difference to mere gothic fiction are the fantastical elements it presents (here in form of the sword-and-sorcery genre).

High Fantasy vs Low Fantasy

Every fantastical story contains elements that are and were - as far as we know - not existent in our “real” world but can be imagined to have existed in the past or that could exist in the present or in the future. They both are imaginative, in opposition to documentative (like mere descriptions of events or observations, “real” stories) and in this sense, they are notional (or “fictitious”) instead of historical (or “traditious”); they are “made up” instead of “handed down”.

In short: they are fantastic instead of realistic. But realistic here means only: “as it was realised in history” or “as it was realised in evolution” etc. But both historical as well as evolutionary developments could have turned out differently; it is in this sense that some fantastical stories or aspects of them can be considered conceivable as “potentially real”, while others may hardly be able to be conceived - based on the world we know - as having any potential of realisation in the past, present or future.

And this is one of the crucial things to differentiate between fantastical stories. Instead of the superficial and outdated differentiations such as fantasy vs. sci-fi, we suggest to differentiate the nature of fantastical stories based on the following differentiations:

- Historicity of the Fantastical: Is it, in spite of its fantastical elements, inspired by or set in a historical period of the past, the present or in an imaginative future based on historical reality? Or is it beyond any historical inspiration in a purely fantastical world? (historically inspired vs. non-historically inspired fantasy)

- Pervasiveness of the Fantastical: Are the fantastical or magical elements in "high" focus of (or especially highlighted in) the story, do they fully pervade the game and the world or are they low-key? (high vs. low fantasy)

- Conceivability of the Fantastical: Are the fantastical elements of the story conceivable as potentially real or decidedly surreal and does the story try to make this conceivability believable by any (pseudo-)scientific means or doesn't it care about that? (down-to-earth-fantasy vs. (airy-)fairy-tale-fantasy)

Obviously the borders between those categorical pairs are fluid and there may be scenarios where we would have a hard time to clearly assign one or the other. But many fantasy universes can be easily assigned to one of the two classes in each category.

Gothic presents an imaginative-past, early-medieval inspired, down-to-earth and low fantasy scenario. While not actually referring to any historical period it is roughly inspired by late ancient / early medieval historical reality based on its architecture, technology, politics, religion etc. In opposition to worlds like Vvardenfell from MORROWIND, where the fantastical elements pervade everything and you’re confronted by them with every step, as it is high fantasy in design - walking through the world of Gothic, apart from the Magical Barrier itself, you are confronted by an apparently very normal place as it could have existed. There are strange creatures, but there are reasons for their existence based on the mysterious Magical and Psionic Emissions of that particular place in the world; neither the Magical Ore nor many of the strange creatures were supposed to be found everywhere in this world, just as the mutants in the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone from STALKER are not supposed to occur everywhere in the world it is set in; they are specifically limited to the Zone.

All the magic in the world of Gothic, including the Barrier, is just as strange for the people living therein and just as rare and mythical for people in other areas of the Kingdom as anomalies and mutants and artefacts are for the people in the world of STALKER outside the Exclusion Zone. While the fantastical and magical elements in high fantasy universes are considered normal by the people in these worlds, Gothic presents them specifically as strange and irregular.

Obviously what is written above is not the case in the official successors of the franchise; they destroyed this openness and the possibility of keeping the fantasy down-to-earth and low by deciding to normalise the fantastical; by not explaining it as anything strange or rare, by expanding the former irregularity of the Colony into the whole world which greatly minimised the meaning of the Colony that was once supposed to be a special place with its unique and strange occurrences; now the magic ore was everywhere to be found as well as all its not-so-special-anymore creatures; what was still open at the time of Gothic was now closed and developed into a very specific direction away from the potential of a down-to-earth low-fantasy scenario.

High fantasy is not just informed by stereotypical fantasy elements such as elves and dwarves, wizards and knights, dwarves and dragons. The main difference to low fantasy is the implicitness of these elements. In a typical high fantasy universe all of these fantastical elements are no source of wonder, myth or belief, are not considered strange; they are implicitly true and normal.

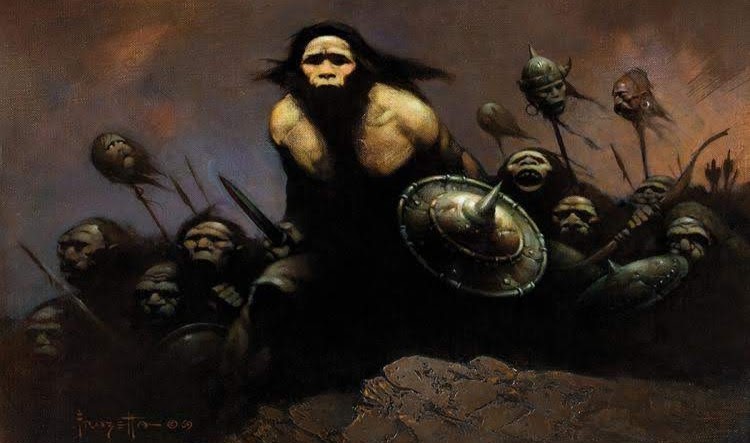

Mike specifically strived to create a fantasy world of creatures not to be found in any other common fantasy universe. Being fantasy of course they were inspired by Lord of the Rings and other popular fantasy fiction, but for him it was essential to make them unique. Originally even the Orcs were not supposed to have that common name. Partly inspired by H.G. Wells “The Time Machine”, the name “Morlocks” was used internally for the Half-Orcs (half men, half orcs) that were originally supposed to be in the game and some of them were to live among the humans. The orcs themselves (according to the early Gothic lore on the official website) were once living with the humans in peace on the surface of the earth. Just as the Homo neanderthalensis coexisted with the Homo sapiens in our world (for ~3000 to ~5000 years in Europe).

“I’ve been speculating that this is why humans have these legends. About orc-like creatures.” (Avallach) As a matter of fact, there was interbreeding between Neanderthals and early modern humans (compare that to the Half-Orc idea of the early vision of Gothic) and violent conflicts with our species is very likely to have been one of the reasons for their extinction.

Compare the painting below by Frank Frazetta (whose works were a major inspiration for the artdirection of Gothic) with this image and the design of the orcs in Gothic.

In Gothic they just continued to coexist. The Orcs developed differently (in an evolutionary perspective) and their culture declined as they started to live deep under the earth for thousands of years because of the racism of the humans and the wars on the surface that has driven them underground, as the early lore informs us.

I have to credit both Avallach and Dmitriy aka Phantom95 for the section above - they both speculated - independent from each other about how the orcs in Gothic may be compared to a co-existing human subspecies.

Other than that, the orcish culture in Gothic is quite different from the one in other fantasy universes. The orcs are more akin to an intelligent primate species like in Planet of the Apes than to the typical blood-thirsty monsters as which they are depicted most of the time. And not to forget about the shamans which play a crucial cultural role and are mainly inspired by real-world voodoo cults.

Yes, there are Skeletons, Zombies, Goblins and Trolls, something like the “staples” of fantasy monsters (but as well part of any folklore and horror story way before modern “fantasy” stories that we usually think of were written). But the Goblins for instance got a very different design. They are no mammals but reptiles with scales and hatch out of eggs. The Trolls are nothing but huge apes, similar to Gorillas (originally they were smaller), as they could have existed in the past, living in synergy with the Gobbos.

Then there are all the actually unique monsters of the Colony: Scavengers and Molerats, Snappers and Lurkers, Bloodflies and Swampsharks, Crawlers and Meatbugs, Shadowbeasts, Orc Dogs and Wolfs. Why Wolfs you may ask? As we wrote before: In the Colony, every monster was supposed to be unique, the wolf being no exception. Only in later versions he was replaced by a conventional wolf design. Some of the monsters are inspired by saurians (such as Scavengers and Snappers), the Shadowbeast is the gothic version of a bear and so on.

At the beginning of the game the player is introduced to a specific monster by a hunter with the words “that is how we call these large birds”. And the reason why the player character has to be introduced to them alongside with the player himself is that they are not common in other realms of the empire, just as many other monsters of this world were not supposed to be. They are unique to Tymoris and known in the Colony in particular, just as the magical ore was supposed to be unique to the Colony and not to be found in other regular mines of the Kingdom; it’s a special kind of ore only to be found in the mines near the City of Khorinis for reasons.

In the Colony there is this “Magical” Ore, in the Colony there are those strange mutated creatures that differ from those in the Outside World. They are unique to the Colony due to the Colony’s specific magical properties and Psi Emissions, the source of which the player was supposed to discover; just as the radioactivity and the Psi Emissions in the zone of STALKER. Outside of the Colony (or rather outside the zone that is affected by the magical influence that has its centre in the Colony) there lies a more “normal world”, just as a “normal world” surrounds the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone.

Morrowind is an example of high fantasy - that is not to be seen as a critique - and in this way it is completely different than the low fantasy that Gothic was supposed to be. There is a bunch of races, including elves, the lizard-like Argonians and cat-like Khajiits. Magic is everywhere and normal. While in Gothic magic is rare, people are afraid of the mages and they do not understand their powers - if they have seen them at all - and no one knows whether or not they were really granted by the gods, as they claim. As in Gothic the gods are not a fact, they may or may not exist; the developers left this question open (in the first instalment).

Low Fantasy reduces the amount of fantastical phenomena, so that those which remain feel more special and more believable at the same time. Another characteristic is that low fantasy does not establish out- or beyond-worldly entities (like gods) as blunt facts.

It preserves at least the possibility of a (pseudo)-scientific or psychological explanation of the fantastical elements it presents, based on our own historical and physical understanding, to reinforce the notion that “it could have been” like that in an unknown past in an unknown kingdom.

And as Arbax pointed out - there is another dimension to it. Based on the importance of amorality of the tale, of a story beyond good and evil, as well as based on some of the statements of the devs about their vision of Gothic, such as “the story of GOTHIC will deal with the question if fate is avertable or not…” or “Phoenix is for those […] who […] are longing for some deeper form of Entertainment” (as much as that may just be marketing speech), we could as well argue that “philosophical fantasy” (probably a less known genre) can be considered part of the early design direction.

Gothic Horror & the target audience

Another underestimated aspect of true gothic fantasy, which is essential for gothic fiction in general, is the horror. While many fans of the franchise do not seem to consider it a substantial part of the game at all [the game was released with an age recommendation of 12 in Germany], this is not representative for the developers’ initial intentions, to make a game for adults. In this interview that becomes especially clear:

[…] And we may discreetly cut it [the German version] compared to the international version, in order to get the USK-rating approved for age 16. (Tom Putzki, Hot Spot, 2/2000, S. 52)

That said, they expected to receive a rating of 18 in Germany if they do not cut the game. The explicit passages and horror elements in Alex Wittmanns novel based on the earlier iterations of the story are also supporting this position. Today Piranha Bytes is talking about aiming for a rating for age 12 “as always”, while back then they expected to get a rating for age 18 if they wouldn’t censor it in Germany. Explicit language, nakedness, sex, orgies, racism, drugs (that you had to take yourself), blood, decapitation… there was enough horror for a gothic story and enough reason for a higher rating, of which not that much was left upon release.

To summarise: Gothic is both dark and low fantasy, but as a genre it is not equivalent to either; while it shares many of their characteristics it also includes the traditional elements of gothic fiction and presents an early medieval inspired world infused with modern gothic style, which in combination represent Gothic Fantasy.

Gothic as an Immersive Sim

Gothic, as any other game, was influenced by games made before. To define or redefine Gothic we have to take the context of game development history into account in which the vision of Gothic arose. Primary influences of Gothic were…

- Ultima Underworld: The Stygian Abyss

- System Shock and

- Thief: The Dark Project

And while these projects are very different in their setting, they are very similar in their design. All three of them were made by Looking Glass. All three of them were milestones in game development. And all three of them were crucial steps in the development of what we call today the “Immersive Sim”.

After those achievements by Looking Glass there were natural next steps to be taken in game development to develop the Immersive Sim further. And several developers attempted to take them with their games. DEUS EX, ARX FATALIS and GOTHIC were the main projects in that tradition at the time (at least that I know of) that attempted to take this very path.

Deus Ex (working title “Troubleshooter”) was described by Warren Spector in his pitch as “Underworld-style first-person action”. The development began in 1997 at the same time as the development of Gothic and it was released in June 2000. It was supposed to be a game that would overcome established genres. Simulation, RPG, First-Person Shooter, Adventure, it was supposed to be all of it.

In the same way, Arkane Studios wanted to make a Sequel to Ultima Underworld; (working title was “Ultima Underworld III”), but as they couldn’t acquire the licence and their proposal was rejected, it would become Arx Fatalis.

The same Immersive Sims inspired both the Mad Scientists, - who wanted to make the “best game in the world” and would later develop the Engine of Gothic - as well as the four founders of Piranha Bytes. They were idealists at that time, in 1997, and Gothic (working title “Phoenix”) was meant to be a combination of all the things they loved. In fact, it would have been just as wild a mix of genres as Deus Ex. In the “Vision of Gothic” I tried to summarise their take on the immersive sim in condensed form.

[…] I really enjoyed old Games like Dungeon Master, Ultima Underworld or SystemShock and I’ve been waiting for an up to date Sequel for a long time, but that doesn’t happen. So: Do it yourself! (Mike Hoge, 29.05.1998, Gamesmania)

GOTHIC was supposed to…

… be a mix of fantasy role playing and action (video) game in realtime 3D experienced in a 3rd person view (and other case-specific modes) with dynamic camera movement where the player is always in control of what he sees (no cutscenes, just an immersive simulated game world).

… not be a typical, “old-fashioned” role playing game, but should utilise the immersive potential of video games as a medium in that it gets rid of statistics and unnecessary abstraction by radical visualisation and interaction, thereby revolutionising CRPGs.

…be “a deeper form of Entertainment” that is “easy to understand but complex” in its possibilities of interaction, because you can interact with everything (items, objects, NPCs), without a complicated interface “due to the game’s clear structure”; it is made for those who like world exploration, action and RPGs (and in this order) with a gameplay that is not supposed to be a “Quake with swords” but tactical and focused on “monster-based puzzles” that have to be solved by direct interaction.

In the next project in development by Mike Hoge ("Unplugged") after Gothic, - and before he had to give it up and work on "Gothic 2" - they even wanted to add the base world itself to the list of interactivity by making the world destructible.

Finster - the original demo by the Mad Scientists that we released in 2022 - was already a mix of sword-and-sorcery and shooter, roleplaying game and action with a minimal interface. And if Gothic would have become everything they wanted it to be, it would have combined a few of the best game recipes in one; it would have been Third-Person and First-Person, it would have come with the best of Roleplay à la Ultima with Action à la System Shock, Adventure and Movement a la Tomb Raider, Stealth like Hitman and Thief combined and a Simulation with more complexity, more interactive AI, with a more living, simulated world and ultimately more immersion than anything seen before. And not to forget, they promised all of that in form of a Singleplayer and a Multiplayer Coop…

Gothic was influential and it is relatively well known, but if it would have been developed into what they originally imagined it to be - it would be mentioned today, without any doubt, in the same breath as Deus Ex and Arx Fatalis. But as it turned out to be released, under the pressure of time and struggles in design, it is now - sadly and unfairly - not even seen in that tradition and rarely ever mentioned when the Immersive Sim is being discussed. And we want to change that.

We may think of Gothic’s gameplay principles as another aspect that is independent from its stylistic elements. But we may as well try to perceive the design principles rooted in the tradition of the Immersive Sim as being consequently deduced from the underlying aesthetics and style and vice versa: the gothic aesthetics as a narrative (or in this context: gameplay) element, a narrative means. In a gameplay that sets exploration first, the atmosphere, mood, style of the world becomes an absolutely essential part of the design. The aesthetics influences the gameplay and the gameplay is built in accordance with the aesthetics; the gameplay can’t be in the way of the aesthetics and the aesthetics can’t be in the way of the gameplay. They have to be combined harmoniously to have gothic-like game design.

A game that comes with a gameplay similar to Gothic but has no gothic aesthetics cannot be a gothic-like, nor can a game that comes with gothic aesthetics but lacks the gameplay characteristics be considered to be a gothic-like. And so we have to conclude that the official successors of Gothic are not abiding by the principles of gothic-like game design.

This is not a judgement on their value as games. What we state here is that they are simply no worthy successors; not only were they even more limited in their immersive sim aspects than Gothic from 2001 - that was itself very restricted in comparison to what was originally planned - they also did not improve any of the essential principles such as the immersion by visualisation. It is a fact that they didn’t do anything to develop Gothic any further as an Immersive Sim. None of its original aspects inspired by the masterpieces by Looking Glass were taken up or refined. Thus, the franchise did not only make no progress in regard to the history of the Immersive Sim, but most importantly it has completely abandoned the gothic aesthetics after Gothic from 2001. They have a gameplay like Gothic, but they aren’t gothic-likes.

The Witcher series, especially Witcher 1, has more gothic aesthetics than any official successor of Gothic (2001) and they have done a great job in the story department too; but while the developers even stated themselves how Gothic has inspired them, all of their games are less of an immersive simulation than any Gothic game. The world of Witcher 3 especially is filled with big, empty buildings of mere scenery, there is no social life neither of monsters constantly spawning for the player and not even of human NPCs (in complete opposition to the idea of a game world without mere scenic buildings and a simulated A-life that is so essential to GOTHIC and STALKER alike). The human behaviour and the repertoire of reactions to the player’s behaviour are extremely restricted in comparison to Gothic, nor can the player solve tasks by different means (as conceived in the vision of Gothic in the form of the classes); it has almost nothing of an Immersive Sim at all. It is hard to imagine that the developers were “inspired” by Gothic as they claim. If so they were inspired only in a superficial way, just as all the recent titles by Piranha Bytes that are claimed to be made with the same recipe as Gothic, that are supposed to be successors in spirit, while they are just blindly copying superficial aspects of it.

There are many examples of games that have a clear gothic aesthetics; less from today than back then (we mentioned several titles above). Dusk, Cliff Barker’s Undying or Call of Cthulhu are some modern examples of gothic style. But while all of those games adhere to gothic aesthetics they are no immersive sims; neither RPG, nor exploration focused, nor offering different creative solutions to a problem; they’re pure action, platforming or adventure games and thus very limited in their modes of interaction.

Gloomwood is an exception in that it is both gothic in style as well as an immersive sim in the tradition of Looking Glass, described as a “Thief with Guns”. Thus it fulfils two of three checkmarks for gothic-like gamedesign. What it does not come with are the four particular RPG elements of GOTHIC: The (1) immersion by visualisation, the (2) complex NPC behaviour and possibilities of interaction, the (3) existence of classes to choose through roleplay, enabling the player to solve the game differently and the (4) “extreme simple user interface” (in relation to the complexity of the roleplay).

Based on the principles of gothic-like game design that we pointed out we have to emphasize over and over again, that there is no game - at least none that we are aware of - that is as gothic-like as STALKER. STALKER shares both the gothic aesthetics and most of its gameplay principles, it is a roleplaying game in the actual sense of the term and an incredible immersive simulation. The release version of STALKER is primarily lacking in the presentation of the story and in the interaction with NPCs and their world, that lacks unique content and more handmade environmental storytelling. GSC Gameworld decided to value the Immersive Sim aspects more than the Story presentation, while the release version of Gothic was lacking in the Immersive Sim aspects that it originally wanted to pull off and Piranha Bytes decided to value the Story presentation more. Just as with Gothic the release version of STALKER was very different to what they originally planned, just as with Gothic the original vision was much more interesting and more appealing than the final product and while we are working on realising the original vision of Gothic as “PHOENIX”, some STALKER modders are working on an Oblivion Lost Remake to this very day. PHOENIX is to GOTHIC what OBLIVION LOST is to STALKER.

Gothic (re)defined

A “gothic” game has by definition to abide by the stylistic characteristics of the gothic art, fiction and culture it is inspired by, which we summarise as “Gothic Aesthetics”. This style is nothing that Gothic as a game invented, but the game is rooted in this aesthetics and the devs went so far as declaring the fantasy world they created from this influence as another kind of fantasy: Gothic Fantasy.

Gothic was created with the ambition to introduce a new kind of fantasy to the medium, to represent a new genre of video games and to develop the immersive sim further. We continue exactly here, where they left off. Only a game that attempts to combine gothic aesthetics and gothic fantasy with an immersive sim approach to RPG design can be considered as a gothic-like game.

As Mike said in 1998: “Fortunately, no one came too close to our vision of a 3D-RPG by now…” Fortunately or unfortunately, we can argue that this statement holds still true today, because Gothic itself came not too close to the vision they had in 1998, that inspires us the most. It is in this sense, that PHOENIX is the new GOTHIC. It was once supposed to be Phoenix and now it becomes PHOENIX again.